Introduction

As organisations expand across the Asia-Pacific region, they must navigate a complex landscape of privacy laws. Japan’s Act on the Protection of Personal Information (APPI), South Korea’s Personal Information Protection Act (PIPA), and Singapore’s Personal Data Protection Act (PDPA) all regulate how businesses collect, use, and transfer personal data, with consent at the centre. Understanding the differences in consent requirements across these laws is critical for compliance and maintaining consumer trust.

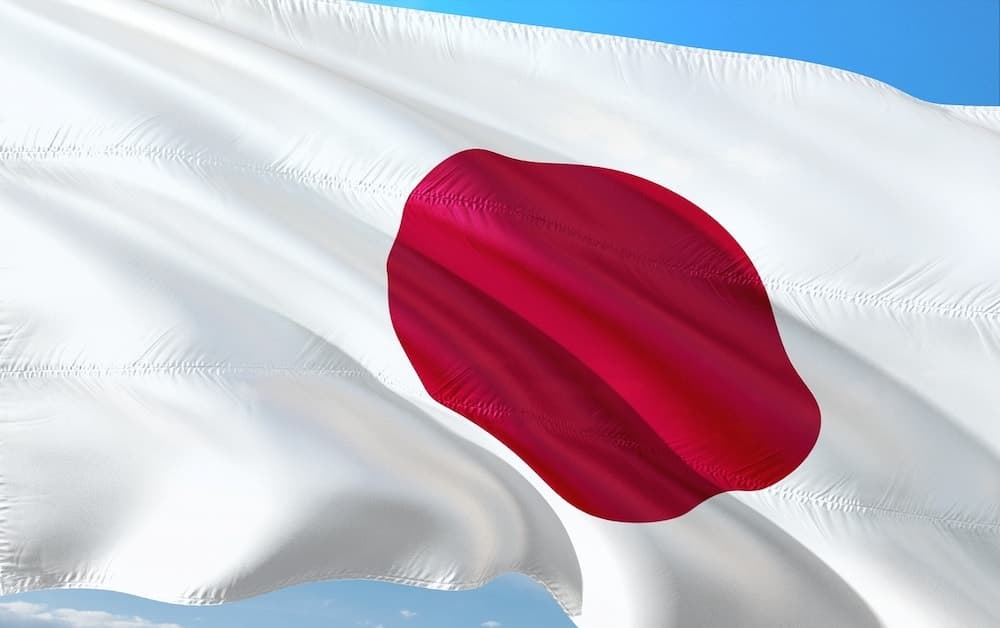

Japan’s APPI Framework

Under APPI, organisations must specify the purpose of data use and obtain consent in certain situations. Consent is required when:

- Personal data is used beyond its stated purpose.

- Sensitive information is processed.

- Data is provided to a third party, including overseas transfers (unless exceptions apply).

Businesses must notify individuals of data usage purposes at or before collection and take security measures to prevent unauthorised access or loss. APPI also grants individuals rights to access, correct, or delete their personal data.

Key takeaway: APPI centres on transparency and prior consent for secondary uses, sensitive data, and overseas transfers.

South Korea’s PIPA Framework

South Korea’s PIPA is one of the strictest data protection laws in the region. It requires explicit consent for collecting and using personal data, with mandatory disclosure of:

- Purpose of collection.

- Categories of data.

- Retention period.

Special rules apply to children’s data, and organisations must adopt strong security measures. PIPA allows limited use of pseudonymised data for research or statistics without consent, provided re-identification risks are controlled.

Key takeaway: PIPA demands explicit, informed consent and strong accountability for all stages of data handling.

Singapore’s PDPA Framework

Singapore’s PDPA establishes a general rule that organisations may not collect, use, or disclose personal data without consent, either express or deemed. Deemed consent applies when individuals voluntarily provide data for a reasonable purpose. Individuals can withdraw consent at any time, and organisations must cease use or disclosure unless another lawful basis applies.

For cross-border transfers, organisations must ensure the recipient provides comparable protection or obtain explicit consent.

Key takeaway: PDPA allows flexibility with “deemed consent” but emphasises transparency and individual control.

Consent Requirements

The notion of consent is central to data protection compliance, but the way in which it is applied differs markedly across the Asia Pacific region. For organisations and data controllers and processors, recognising these distinctions is vital, especially around how consent is defined, when it is required, how it may be withdrawn and how it interacts with data transfers and automated decision-making.

What is “Consent”?

At a high level, consent means an individual’s agreement to the processing of personal data for a specified purpose. In an Asia Pacific context:

- It must often be informed, meaning the individual is made aware of the purpose, categories of personal data, retention period, disclosure or transfer to third parties and the right to withdraw consent. Under PIPA in South Korea, a personal information controller must disclose these details when obtaining consent.

- It must be freely given, meaning the individual has a genuine choice. Some laws allow for deemed consent, as under Singapore’s PDPA, which complicates compliance.

- Consent often must be specific for particular processing or transfers beyond the original scope. Under APPI, if personal information will be used beyond the original purpose or given to a third party, prior consent is required.

Variation in consent across jurisdictions

Let’s compare how the three regimes handle consent: APPI (Japan), PIPA (South Korea) and PDPA (Singapore).

- Japan (APPI): Consent is required in defined circumstances, such as for sensitive data handling, third-party transfers or use beyond the original purpose. Consent is typically explicit, meaning affirmative action such as ticking a box or signing a form. There is no fully articulated legitimate interests basis in the same sense as European law.

- South Korea (PIPA): The law requires consent for the collection and use of personal information. At the time of obtaining consent, the data controller must disclose purpose, categories of personal information and retention period. The law also includes specific obligations when processing children’s personal information and unique identifiers.

- Singapore (PDPA): The law prohibits the collection, use or disclosure of personal data unless consent (actual or deemed) is given. The PDPA defines consent as the individual being notified of the purpose and having provided consent. Consent can also be deemed where the individual voluntarily provides their personal data and it is reasonable to do so.

Rights to withdraw consent and access

In many Asia Pacific regimes, an individual has the right to withdraw consent or exercise rights of access, correction and deletion. For instance:

- Under Singapore’s PDPA, individuals may withdraw consent at any time. Organisations must stop collecting, using or disclosing personal data after withdrawal unless another legal basis applies, and they must inform the individual of any legal or business consequences.

- Under Japan’s APPI, consent for transfer of personal data outside Japan must be given, and data subject rights include access and correction, though the mechanism for withdrawal is less explicit.

- Under South Korea’s PIPA, the data subject has rights such as access, correction, deletion and objection, and the law requires notification of these rights when obtaining consent.

Consent in the context of automated decision-making, sensitive data and transfers

In the Asia Pacific region, processing of sensitive data (such as health, criminal or biometric data), automated decision-making, profiling and cross-border data transfer often trigger heightened consent obligations.

- Under APPI, special-care required personal information (sensitive data) demands prior consent.

- Under PDPA, purpose limitation and reasonableness obligations apply when using personal data for decision-making or disclosures; accuracy is emphasised when data is used to make decisions affecting individuals.

- Under PIPA, pseudonymised information may be processed without consent for research or statistical uses, but controllers must ensure de-identification and restrict identifying individuals.

Further, when transferring data overseas, Singapore requires that organisations take reasonable steps to ensure comparable protection in the recipient country and sometimes obtain written consent from the individual. Japan’s APPI similarly requires consent for overseas transfers unless certain safeguards or equivalence apply.

Comparing Consent Across APPI, PIPA, and PDPA

Aspect | Japan (APPI) | South Korea (PIPA) | Singapore (PDPA) |

|---|---|---|---|

Type of Consent | Explicit in specific cases (e.g., sensitive data, third-party transfers) | Explicit and informed for most processing | Express or deemed consent |

Key Requirements | Notify purpose of use; obtain prior consent for extra processing or transfers | Disclose purpose, categories, retention; obtain prior consent | Notify purpose; allow withdrawal; deemed consent for reasonable uses |

Withdrawal of Consent | Implied through rights to correct/delete | Explicit right to withdraw at any time | Explicit right to withdraw; must stop use/disclosure |

Sensitive Data | Requires prior consent | Requires separate consent | Treated with higher protection; consent still required |

Cross-Border Transfers | Consent unless equivalent protection applies | Limited, requires safeguards | Must ensure comparable protection or obtain consent |

Best Practices for Compliance

To support compliance efforts across the Asia Pacific region, organisations should adopt holistic practices that align with the core tenets of data protection, while tailoring them for specific jurisdictional demands.

Transparency, user control and consent management

- Use clear and concise language in consent notices, privacy policies and disclosures. Organisations must make sure users understand what personal data is being collected, for what purpose, for how long, with whom it may be disclosed or transferred, and how they can withdraw consent or exercise rights.

- Ensure prior notice and obtain consent (where required) before collecting, using or disclosing personal data, especially for sensitive data, cross-border transfers or automated decisions. Preserve records of consent including who gave it, when, for what purpose, what the version was and how it was obtained.

- Facilitate withdrawal of consent and ensure users can easily exercise their rights such as access, correction, deletion or objection. Organisations must have processes in place to stop collection, use or disclosure following withdrawal unless another basis applies and must notify the individual of consequences.

- Conduct purpose limitation assessments to define specific, legitimate and transparent purposes for personal data collection and processing. If new processing or transfer arises outside the original purpose, obtain additional consent or notify the data subject.

- Be mindful of automated decision-making and profiling. If using personal data for automated decisions such as credit scoring or targeted marketing, ensure transparency and oversight consistent with local law and individual rights.

Security measures, record-keeping and data transfers

- Implement robust security measures to safeguard personal data, including encryption, access controls, secure disposal and pseudonymisation where appropriate. These measures help protect sensitive data and support breach-response preparedness.

- Maintain accurate records of all processing activities including purposes, categories of personal data, disclosures, transfers, retention periods, data subjects’ rights exercised, security incidents, consent records and third-party processor relationships. These records support audit, accountability and regulatory compliance.

- When engaging in cross-border data transfers, implement appropriate safeguards such as transfer agreements, standard contractual clauses, certification under relevant schemes and documented individual consent where required. In the Asia Pacific, transfer obligations differ by jurisdiction.

- Periodically review and update policies, procedures and processing maps. Data protection regulations in the region are evolving, and new amendments can introduce new consent requirements or obligations regarding children’s data, pseudonymisation, automated decision-making or cross-border transfer.

Governance, training and organisational embedding

- Assign or designate a data protection officer or equivalent role, particularly for organisations operating across the region or processing large volumes of personal data. This person helps monitor compliance efforts, liaise with regulators, maintain records and handle data subject requests.

- Provide training to employees, data controllers, data processors and business units to ensure awareness of local data protection laws, consent regimes, handling of sensitive data, breach-notification mechanisms and transfer obligations.

- Embed privacy by design and data protection impact assessments (DPIAs) where applicable. For new projects, services or processing that involves personal data, conduct DPIAs to evaluate risks, consider purpose limitation, minimise collection, anonymise or pseudonymise where possible and document decision-making.

- Keep compliance efforts ongoing by maintaining a regulatory watch in each jurisdiction of operations, monitoring market developments, updating processes when laws change, performing audits or internal reviews, and ensuring third-party processors are compliant.

Conclusion

In the dynamic and interconnected markets of the Asia Pacific region, data protection compliance is not just a legal requirement but a foundation for business trust, operational resilience and cross-border growth. Understanding the key differences in consent requirements and broader data protection obligations under laws like Japan’s APPI, South Korea’s PIPA and Singapore’s PDPA empowers organisations to process personal data responsibly, disclose practices transparently, safeguard personal data appropriately and establish robust compliance efforts.

By focusing on transparency, informed and specific consent, robust security measures, accurate processing records, effective governance and adaptive compliance frameworks, businesses can manage the complexities of the region’s data protection laws. Organizations that align with the spirit and substance of these laws, respecting data subjects’ rights, protecting sensitive data, and maintaining accountability, not only mitigate non-compliance risks but also strengthen consumer confidence and long-term success in the Asia Pacific digital economy.